An ongoing discussion in the Mindfulness and Psychotherapy Study Group has investigated the similarities of mindfulness-based psychotherapy and EMDR. We've noted that the EMDR protocol asks the client to become deeply aware of present moment experiences, including thoughts, feelings, and bodily sensations, and to track those experiences as they change over time. Clearly, in this moment-by-moment awareness, a substantial degree of mindfulness is being elicited in EMDR treatment. Even the act of tracking a moving finger with the eyes requires a sustained contact with present moment visual sensation, and can be considered a mindfulness practice.

Now, there is some interesting research exploring the therapeutic mechanisms in both EMDR and mindfulness practice. Marcel van den Hout and colleagues (2011) have just published a paper whose title says it all: "EMDR and mindfulness: Eye movements and attentional breathing tax working memory and reduce vividness and emotionality of aversive ideation."

This study demonstrated that putting one's attention on either breathing or eye movement essentially takes up some of the available mental bandwidth. The authors at Utrecht University suggest that this is a possible explanation for the increased emotional stability found in mindfulness and EMDR practices. While attending to breathing or eye movements, they argue, we just don't have the mental capacity to pay as much attention to emotions or distressing imagery. They found that breathing and eye movements taxed working memory to the same degree, and had similar (but not identical) effects on a person's experience of emotional distress.

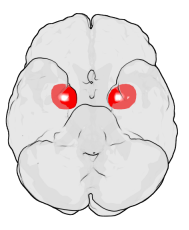

This makes a lot of sense, and this finding dovetails with another discussion we have been having, about the way the brain processes different kinds of information. We know from the work of Farb and colleagues (2007) that different areas of the brain are involved in processing sensory experience and abstract thought or imagery. Thus, adding eye movements or mindful breathing to an emotional experience would shift the location of brain activity away from the "narrative" areas responsible for "aversive ideation," and instead engage areas dedicated to a more sensory level of processing. With a greater "experiential focus," we are less able to generate an emotionally reactive state because we are more grounded in the realistic, sensory, and non-ideational level of experience. It may be that the stabilizing effects of mindful breathing or eye movements come not simply by "overloading" the brain's information processing capacities, but by actually processing experience in a different way.

Buddhist psychology (or what modern psychology is beginning to refer to as the "Buddhist Psychological Model") suggests that mindfulness keeps us in contact with things as they really are by interrupting the processes of mental proliferation that create misunderstanding and reactivity. In mindfulness, we are grounded in what is "really real," as it were, and less carried away in our imagination, prejudice, and reactivity. Current scientific research into the psychology of mindfulness is beginning to suggest ways in which this process is supported at a neurobiological level. In future discussions in the study group, we will be exploring ways to bring this scientific knowledge into the consulting room, and find more effective ways of modelling and evoking mindfulness in the therapeutic relationship.

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_e.png?x-id=d3f6d8cc-8fa3-438c-9301-1984382a5444)

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_e.png?x-id=aca7fd1c-b5ea-48aa-84af-9ec739a0ad3d)

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_e.png?x-id=1b383316-c37c-4864-b537-390ac497fd4d)

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_e.png?x-id=43a1c6bb-f88c-4e3e-ab44-5a7639cd943f)

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_e.png?x-id=4f39269c-0251-4cb0-9ffe-852c4055cc69)

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_e.png?x-id=ba7be2dc-7233-4e30-b759-2d3b43ee3623)

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_e.png?x-id=a4475990-331c-4dfe-b76c-5cc1354cf642)